Access to Tools

March 2021

Text: Nina Sarnelle

As Gods_

“If there’s a fight, then, I will fight. And fight with a purpose. I will not fight for America, nor for home, nor for President Eisenhower, nor for capitalism, nor even for democracy. I will fight for individualism and personal liberty.”

The quote above is taken from the 1957 diary of a 19-year-old freshman at Stanford University who was filled with fear that a Soviet invasion was imminent. In his comprehensive history From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network and the Rise of Digital Utopianism, Fred Turner attributes Brand’s anxieties to a distaste for both the Cold War enemy and his parents’ generation: “the army of gray flannel men who marched off to work every morning in the concrete towers of American industry.” Both the military and the corporate world “moved according to clear lines of authority and rigid organizational structures,” pushing a young Stewart Brand toward the art world, where he saw a system driven by “networking, entrepreneurship, and collaboration,” Turner suggests.

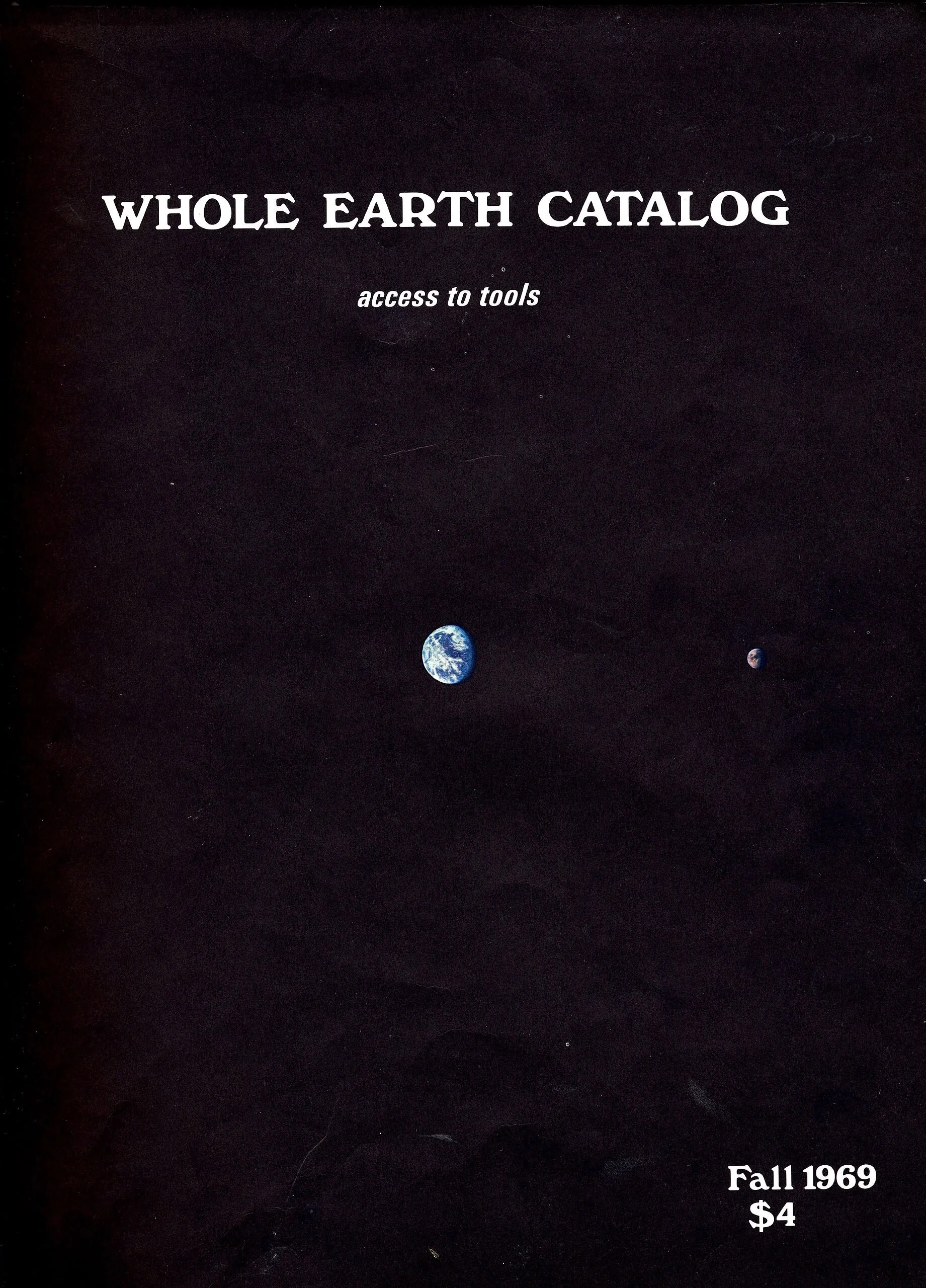

In the late 1960s, Brand published the first Whole Earth Catalog (WEC), a magazine and product catalogue that would become “one of the defining documents of the American counterculture” (Turner, 2006). The publication advocated for self-sufficiency, back-to-the-landism, alternative education models and holism, centring on the slogan “access to tools.” Fred Turner describes the catalogue as a “network forum—a place where members of [different] communities came together, exchanged ideas and legitimacy.” Alan Kay and other early computer innovators saw the Catalog as a hyperlinked information system: “We thought of the Whole Earth Catalog as a print version of what the Internet was going to be” (ibid). Apple co-founder Steve Jobs once famously referred to the publication as “google before google.” In 2018, Anna Wiener reflected on the Catalog’s relationship to tech culture in the New Yorker:

“Stewart Brand doesn’t have much to do with the current startup ecosystem, but younger entrepreneurs regularly reach out to him, perhaps in search of a sense of continuity or simply out of curiosity about the industry’s origins. The spirit of the catalogue—its irreverence toward institutions, its emphasis on autodidacticism, and it’s sunny view of computers as tools for personal liberation—appeals to a younger generation of technologists. Brand himself has become a regional icon, a sort of human Venn diagram, celebrated for bridging the hippie counterculture and the nascent personal-computer industry.”

For Turner, it was the Whole Earth Catalog, functioning simultaneously as a platform, a system of beliefs and a network of contributors, that “helped create the cultural conditions under which microcomputers and computer networks could be imagined as tools of liberation.”

Despite a relatively short run, the Whole Earth Catalog inspired many subsequent iterations, and the network it created went on to organize projects like the WELL and Wired Magazine. This essay will map out a context for a newer spin-off, a 2021 art project that I co-created. Called The Whole Sell, it reframes the Whole Earth Catalog as an e-store. This platform confronts contradictions inherent in the Catalog that were present all along, but further crystallised as its logic (and its founder) became central to the development of Silicon Valley in the 80s and 90s. Part publication, part marketplace, The Whole Sell hosts over thirty screen-based artworks, setting up an artist-defined barter system in order to initiate broader conversations about value and transaction.

Today, the Whole Earth Catalog invites both adoration and criticism. With its iconic graphic design and a dreamy kind of charm, it’s a beloved hipster coffee-table book, but I cannot flip through its pages without a certain degree of cynicism. Did Stewart Brand really believe he could instigate cultural revolution with a catalogue? Does anyone see anything wrong here? To anyone with critical opinions about “ethical consumption,” “corporate responsibility,” and “sustainable growth,” the idea of tackling planetary problems by connecting people to more rugged boots seems laughable, at best. But for me, it is the opening line from the Catalog’s statement of purpose that prompts a visceral cringe: “We are as gods and might as well get used to it.”

Whole Earth Catalog Statement of Purpose, 1968 (Image copyright Whole Earth Catalog)

I had to revisit that a few times to make sure I read it right. Intended to empower the self-made homesteader to “conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, and shape his own environment,” this statement blasts through the WEC’s typical hyperbole toward a much more unsettling type of hubris. Sure, some things just don’t age well; but this is no semantic slip. It is precisely this kind of unbridled, adventurous, even arrogant, spirit, threaded throughout the Catalog, that nurtured and shaped the technocrats we know today. In subsequent decades Brand’s focus shifted to the glorification of the “hacker,” who he envisioned as a kind of cowboy, a member of “a mobile newfound elite… scouting a leading edge of technology… [in] outlaw country, where rules are not decree or routine so much as the starker demands of what’s possible” (Turner, 2006).

The statement of purpose above clearly outlined the constraints of the WEC’s rhetorical imagination, clinging to an ardent belief in the “power of the individual” above all else. This turn toward the self as the primary site of transformation followed the ideals of a movement against cultural conformity, one that would eventually coalesce around personal computing as a form of decentralised power. Here we can identify the seeds of a neoliberal revolution that, in the decades following WEC, cast the individual as the root of all success and failure, choice and responsibility. This ideology would develop in the West through Thatcherism and Reaganomics, initiating the dismantling of the welfare state, the war on crime/drugs, big tech monopolies, racist state violence—and it helps to explain some of the deep inequalities of our time.

Soft Organic Sell_

“I’ve yet to figure out what capitalism is, but if it’s what we’re doing, I dig it”

The Whole Earth Catalog was particularly ahead of its time in the way that it integrated commerce with essays on ecology, community, resilience—in other words, with cultural and intellectual content. According to a Garage Magazine piece, WEC’s creators positioned themselves “not only [as] idealists but as curators and tastemakers.” Information on where to purchase hand tools might sit comfortably next to the “Mind of the Dolphin.” The Catalog’s densely-packed pages instructed readers not only on what to buy, but what to know about, what to care about, and what to want, in all senses of the word.

Products were not directly sold in the Whole Earth Catalog but rather ‘reviewed’ in a first-person, conversational tone. Today I’m reminded of this approach whenever I’m listening to a podcast and the host pauses the story to read advertisements aloud, infusing them with personal anecdotes and using their own voice. This voice feels so close, intimate and real: it’s the voice I’ve come here to listen to. Maybe I should try this one-time Squarespace offer code? For the critical consumer, a casual reco from a friend or “like-minded” celebrity is infinitely more persuasive than an unsolicited YouTube ad. There’s a whole industry of guerilla and viral marketing built around this premise. It’s about trust, and a kind of self-identification that flows through the vernacular and handmade. The Whole Earth Catalog is filled with this idiosyncratic feeling, from its hand-written chapter headings to its purging of the elitist “white space” of traditional graphic design. Indeed, the aesthetics of quirk appealed to late-sixties “rebel” consumers long before it leaked through the cracks in my armour. Fifty years later, savvy contemporary ad agencies have honed an arsenal of techniques like these, going so far as to replace commercials altogether with branded content or cultural programming. In the age of the “lifestyle brand,” strategists know very well that they are no longer just selling products, but rather ideas, critique, vibe, stories, identities and values. Sometimes they fall on their faces, but more often than not, they end up selling a shit-ton of sneakers.

We_

“We are creating a world that all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth…. Your legal concepts of property, expression, identity, movement, and context do not apply to us. They are all based on matter, and there is no matter here.”

“We Are All One. ”

The first quote above is from John Perry Barlow’s Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace in 1996; the second is the slogan of USCO, an art collective that Stewart Brand worked with in the early sixties. In the shadow of these monolithic “we”s, it’s worth taking a moment to consider who exactly the Whole Earth Catalog was speaking to. After decades of damage wreaked by the colourblind, ableist, gender-normative universalism that functions to prop up the false meritocracy of neoliberalism, today we must pay attention to basic demographics.

Whole Earth Catalog, 1968, book review of Surface Anatomy depicting the universal “human creature” in exclusively light-skinned portraiture. “How cliche ridden our usual views of ourselves are,” it reads (face-palm).

Who were the Catalog’s writers and readers? Over the years, the WEC’s editor list included names such as Lloyd Kahn, Gurney Norman, Gordon Ashby, Paul Krassner and Ken Kesey, alongside Stewart Brand. Now, what demographic consistencies might we find among these individuals? A couple of quick google searches will answer that question: white, male, middle-class, affluent. A casual flip through the pages of the Whole Earth Catalog also reveals a distinction between depictions of its presumed audience, and depictions of ancient knowledge to be consumed, or exoticized cultures to be appropriated: the “us” and the “them.”

Whole Earth Catalog, 1968: the “US.” While precise demographics are not easy to discern in the B&W prints of the publication, it’s easy to see the WEC’s self-identification with a young, white, straight, cis-gendered, able-bodied readership.

At the same time, the Catalog’s distinctive techniques of juxtaposition and collage, cross-disciplinary connection and “legitimacy exchange” allowed its reader to imagine himself “simultaneously ancient and contemporary. He is an Indian; he is also an engineer.” (Turner)

Whole Earth Catalog, 1968: the “THEM.” The “Learning” Chapter features book reviews of Survival Arts of the Primitive Paiutes, The Teachings of Don Juan, Fundamentals of Yoga, and The I Ching, a greatest hits of Western cultural appropriation.

In Daughters of Aquarius: Women of the Sixties Counterculture, Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo depicts the hippie movement in starkly racial and socio-economic terms: “more than half came from middle-class families, and fewer than 3 percent were non-white.” In their 1995 critical essay The Californian Ideology, Barbrook and Cameron explain that to West Coast ideologues, a “utopian vision of California depends upon a wilful blindness towards the other - much less positive - features of life on the West Coast: racism, poverty and environmental degradation.” Fred Turner’s description of the “cowboy nomads of the communes” also aligns with these analyses, and he asks a critical question that still hangs in the air today:

“What kind of world would this new elite build? To the extent that the Whole Earth Catalog serves as a guide, it would be masculine, entrepreneurial, well-educated, and white. It would celebrate systems theory and the power of technology to foster social change. And it would turn away from questions of gender, race, and class, and toward a rhetoric of individual and small-group empowerment.”

It’s no wonder that, amidst all of the Whole Earth Catalog’s radical whimsy, one can detect more than a hint of uncritical settler mentality (although its subscribers might prefer the term “pioneer”). From the Catalog’s spreads devoted to L.L. Bean, Sierra Club and National Geographic to today’s #VanLife enthusiasts and survivalist preppers, the roots of self-reliance culture are deeply colonial and individualistic; they reach all the way back to the invention of “nature” as an oppositional force to be cultivated or tamed by white cis masculinity.

Alongside scientific exploration and new age philosophy, the WEC peddled a quasi-libertarian ethos based on a naive blend of DIY meritocracy and tech optimism: the same ethos that inspired the founding fathers of Silicon Valley. Those nerdy garage “visionaries” publicly performed a kind of upwardly-mobile American Dream that blandly denied systemic injustice and inequality. Are we supposed to believe it is coincidental that all of our early tech innovators were upper/middle-class white men with a similar education, many of them having attended the same university? Were people of colour, poor people, women, disabled folks just not “into” computers? In a sickening twist of circumstances, poor labourers, workers of colour and women—often unseen, often overseas—would eventually fill the ranks of dehumanised labour responsible for manufacturing the consumer tech products invented in California. In Fred Turner’s words:

“The rhetoric of peer-to-peer informationalism… actively obscures the material and technical infrastructures on which both the Internet and the lives of the digital generation depend. Behind the fantasy of unimpeded information flow lies the reality of millions of plastic keyboards, silicon wafers, glass faced monitors, and endless miles of cable. All of these technologies depend on manual laborers, first to build them and later to tear them apart.”

Like so many of Silicon Valley’s ideological slogans (such as “information superhighway” or “global village”), WEC’s tagline “access to tools” has now been problematised by fifty years of real-world complications. The sentiment is there, but the words ring hollow. Continents away from the Catalog’s cybernetic dreaming, a critical mind today might ask: What have all of these tools brought us? Surveillance, mass data collection and algorithmic oppression? The commodification and gamification of every part of our lives? The heightened alienation and polarisation of our filter bubbles? A hierarchy of clicks that elevates hate, abjection and lies? While Silicon Valley imagined future humans shaping their world with tools, over time we’ve begun to better understand the ways in which these tools shape us. The trajectory of consumer tech design has shifted decidedly toward an obfuscation of ‘how things work,’ replacing what Brand imagined to be empowered learners/makers with passive, dependent consumers. Furthermore, Silicon Valley’s near-monopoly on new tech development means that its products and services are exported worldwide, structuring the communication, privacy, safety and knowledge of people all over the earth. The world re-designed by Silicon Valley was supposed to be “decentralized, egalitarian, harmonious, and free” (Turner); instead we’ve watched multinational corporations inflate with centralized techno-colonial power.

Many creative thinkers still feel an affection for the Whole Earth Catalog, but today it’s just not possible to live in a world described by its selective optimism. We are less interested in Richard Brautigan’s All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, than in Adam Curtis’s 2012 series of the same title. Reflecting on the spirit and hope contained within the Catalog’s soft covers, The Whole Sell provides an update for the world we understand today while thinking critically about what/who might have been excluded from the WEC’s vision of the future.

Left to right: Stewart Brand wearing a sandwich board in 1966; the button he made for the campaign; Brand holding the button many years later. (Images found online)

Donut Holes_

The “Whole Earth” of the Catalog’s namesake comes from a 1966 performative project by Stewart Brand in which he campaigned for NASA to release the first satellite image of the entire Earth taken from space. When the photo was released in 1967 it was used to create the Catalog’s iconic cover design.

The Whole Sell has adopted a more recent breakthrough in cosmic imagery: the first photographic representation of a black hole. The “donut,” as it’s been called on the Internet, was met with equal parts awe and disappointment when it was first published in 2019. But should we be surprised by the unphotogenic quality of a phenomenon that can’t actually be seen? What exactly are we “seeing” when we “look at” a black hole? Is the metaphor of vision even relevant? In The Terraforming Benjamin Bratton explains that:

“The thing we see as an “image” was constructed from data produced not by a conventional camera, but by Event Horizon, a network of telescopes harmonized to focus on the same location at the same time… The mechanism is less a camera than a vast sensing surface: a different kind of difference engine. What we see in the resulting image is the orangey accretion disc of glowing gas being sucked into the void of M87*, outlined by all the non-void it is about to consume… The Black Hole image is a kind of “world picture” that is crucially not a picture of our Earth, but rather a picture taken by the Earth of its surroundings—for which we served as essential enablers.”

The Blue Marble and other NASA images of Earth became a symbol of the 1960’s growing environmental movement. Stewart Brand had high hopes for the potential of this imagery to shift perception from localized concerns toward an ecological planetary consciousness. Indeed, psychologist Frank White coined the term “overview effect” to describe the cognitive shift in awareness that results from the astronaut’s experience of viewing Earth from afar. Brand characterized these photos as a kind of mirror, suggesting that seeing the whole Earth “might tell us something about ourselves.”

And yet the lofty poetics of the WEC were always silently circumscribed by privilege and anthropocentrism. Gil Scott-Heron’s 1970 Whitey on the Moon lends a healthy perspective to Brand’s cosmic gaze: it’s easy to “think globally” when your immediate survival is not in question.

50 years later, Benjamin Bratton offers an additional reading of the “whole earth” viewpoint, critiquing it as a reprise of the centrism and exceptionalism of the flat earth/centre of the universe theories that dominated Western thought until Copernicus. In Bratton’s view, the intimations of precarity and preciousness described by astronauts experiencing the overview effect can only be understood from a narrow human subjectivity: the blue marble is “an icon of geocentrism.”

The cover of The Whole Sell swaps out Stewart Brand’s whole earth photograph for the blurry, bewildering, fundamentally empty cosmic image of our day. Perhaps this spiraling, inescapable implosion, markedly underwhelming on Twitter, is as fitting a current cultural symbol as the blue marble was to the psychedelic awakening of its time? It’s worth considering why the black hole image elicited such a negative public response. The photo’s disappointment derives from its indecipherability: how little it resembles the high-res renderings we’ve seen in action movies, and how little it tells us about ourselves and the world we know. It’s a really crappy mirror. In Bratton’s words,

“The darkness of a black hole is absolutely empty, so part of what makes this image significant is that it signifies true nothingness. The image is the opposite of what they call a mirror, in that it shows them not themselves in the world, but the abyss in which they can never be reflected… ”

Perhaps we might benefit from a bit less time spent mirror-gazing? In this age of climate collapse and accelerating crises, it could be worth taking a realistic look at the future of this star we call the Sun, the actual center of our solar system. The “donut” provides a sober reminder that life only exists in relation to its opposite, an opposite that is both vast and indifferent to our existence. Bratton calls it a “terrifying image.”

Money on the Wall_

“I like money on the wall. Say you were going to buy a $200,000 painting. I think you should take that money, tie it up, and hang it on the wall. Then when someone visited you the first thing they would see is the money on the wall. ”

Entering The Whole Sell website, you are presented with the architecture of a simple online store. However, like the original Whole Earth Catalog, no money changes hands on this site. The items on offer are artworks, and the means of purchasing include neither credit card nor Paypal. Appraising artists’ production using alternative forms of currency, the project explores the relative value of interaction, creative response, and conversation. The platform places visitors and artists into a direct exchange with one another.

Slower modes of user-interaction existed within the Whole Earth Catalog as well, especially in the Supplement, which featured submissions from readers and directories of projects and ways to get involved. But the instantaneous online structure of The Whole Sell more closely recalls dynamics within the WELL (Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link). Started by Stewart Brand and Larry Brilliant in 1985, THE WELL was an early virtual community through which participants interacted and shared ideas in text. Members reported a complex interplay between social, intellectual and economic activity, as their public statements were picked up in the press, shaping reputations and creating powerful networks. They became the “influencers” of the 1980s. This blurring of work, play and passion is familiar to artists, community organizers, and anyone whose work provides more than just money. According to Fred Turner,

“[The] informational gift economy on the WELL depended not only on the expectation of ultimate reward, but also on an intangible feeling that one was working to construct a new sort of social collective… The gift encodes multiple social and economic meanings…[that] are an “open secret” to participants in the system...the rhetoric of community provided the ideological cover necessary to transform a potentially stark and single-minded market transaction into a complex, multidimensional act.” (emphasis mine)

Add to these complexities the often-strained relationship between commerce and art, and a purchase on The Whole Sell platform tends to leave both buyer & seller with more questions than answers: What is cultural capital? How and why do artists sell ideas? What’s the difference between interaction and transaction? And perhaps, most fundamentally: is it possible to subvert capitalism from within, using its own tools, platforms and language?

Artists must be paid for their labour. So long as we live in a society that requires money for survival and equates the value of a human life with an individual’s ability to sell their own labour-power for a wage, it would be ludicrous to demand that artists live in any other way. Many contemporary artists have taken up precarity and injustice as subject-matter, or as mandates to organise in solidarity with others. These projects help to dispel the myth of the artist as solitary genius, immortalized in Oscar Wilde’s quip: “art is the most intense mode of individualism that the world has known.” On the contrary, these artists establish discussions and mechanisms for mutual struggle and survival.

Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.) is a rare attempt at labour organising in the US art world, providing advocacy, data and standards for artist fees, while working to educate artists, artworkers, gallerists and employers. Image copyright: wageforwork.com

Sarah Jaffe’s 2020 book Work Won't Love You Back explains that it can be “difficult for artists themselves to conceive of their problems as collective issues, rather than individual ones. Artists… tend to be more anti-authoritarian than explicitly political.” If this is true, they have a lot in common with the counterculturalists of Stewart Brand’s generation. As Turner describes them, Brand’s “New Communalists turned away from political action and toward technology and the transformation of consciousness as the primary sources of social change.”

Decades earlier, in the 1930’s, Peyton Boswell, the editor of the influential Art Digest, found the idea of unionisation antithetical to the artistic impulse. The artist, he argued, is not a “group man… the very nature that leads him to be an artist makes him intensely individualistic. To such men the very thought of unionization is distasteful. They are not the same as coalminers. The loss of personal initiative means the loss of creative spirit.” (Jaffe, via A. Joan Saab) Here, Boswell's equating of freedom and creativity with individualised participation in a capitalist market, unbound by the burden of collective organising, provides a perfect alibi for neoliberalism, long before its advent. At face value, his statement reeks of condescension, placing artists above coalminers on some kind of bizarre labour hierarchy. However, if a coalminer deserves pay and an artist does not, who is actually higher on Boswell’s invisible ladder? The apparent elitism of his claim serves to obfuscate its true meaning: that artists are not deserving of solidarity or collective bargaining, because the work they do is not really work.

Jaffe’s book articulates the ways that substituting love, fulfillment, meaning, or relationships for compensation in the workplace can become a dangerous proposition for domestic workers, teachers, non-profit workers, service workers and artists alike. This issue disproportionately impacts women and workers of colour. The “labor of love,” as she describes it, is a contemporary form of coercion that has grown up alongside the neoliberal work ethic. It turns workers’ passion for their work against them:

“Sociologist Andrew Ross calls this “sacrificial labor,” the way that one gives up certain facets of stability in order to pursue work that is seen as meaningful… Work would be exciting, fulfilling, creative, a place for self-expression, but you had to give up knowing where your next check was coming from. [Artists] have been sold the idea that not having a boss is liberation… [but it also] limits their ability to organize for better conditions. Upon whom are their demands to be made? (Jaffe)”

As I sit here hammering out this essay late into the night—because I “want to,” not because anyone is forcing me, or even paying me—the irony is not entirely lost.

I am also drawn to Jaffe’s formulation of art as a privatisation of creativity, a resource that we otherwise might hold in common. The artistic discipline, with all of its interlocking systems of education, professionalisation, institutions, nepotism, fetishism and celebrity, functions to commodify one of the most basic attributes that make us human. Sarah Jaffe writes:

“Creativity ... has been turned from a basic human quality, one that anyone is capable of expressing, to a private preserve, enclosed behind the boundaries of its own world. The narrative that artists will create solely for the love of it...is used to justify a variety of exploitative practices rather than to call for an opening up of art worlds to all.”

In the years immediately following the Whole Earth Catalog (in which Stewart Brand championed the self-made, non-conforming individual) the art world's emblematic meritocracy accelerated. According to Jaffe, the 1970s saw a boom in the private art market, “fetishizing the individual artist while cutting off all the legs of state support.” This flood of capital, like all ‘trickle-down’ economics, provided far less than a trickle for most artists and art workers. “Almost nobody could pay rent from art,” Lucy Lippard said at the time. Jaffe, again:

“A few stars became famous and sold works for fabulous sums; the rest of the field looked on longingly from their part-time jobs and crumbling apartments. Art stars became mini-industries in themselves, hiring workers themselves in order to produce works of art. How could such artists be in solidarity with the working class?... The artist became the ideal worker for the neoliberal age just as neoliberalism made it harder and harder to succeed as an artist…it is necessary to have a few superstars visibly raking in the money, and it is necessary to continue to depict art as an end in itself. In the space between these two joys—the anticipated thrill of success, and the pleasure of the art-making itself—most artists get lost.”

It is against this complex history that The Whole Sell attempts to create a space for momentary freedom from the free-market; to poke a hole in the suffocating fabric of capitalist realism, and dance for a moment in the light that pours through. The artworks housed on the site are intentionally small, quick gestures—some of them can be found freely elsewhere online—and many were not made specifically for this platform. For most publications, non-exclusivity would not be something to celebrate, but here it is asserted as anti-exclusivity. This publication is engaged in eroding basic pillars of supply and demand: the foundation of scarcity, authenticity, and celebrity that the art world’s value system is built on.

At the same time, The Whole Sell's yard-sale mentality is meant to provide a low-risk environment for playing with the ways that artist’s ascribe value to their own work, and to the work of others. In adapting their projects for the website, each artist was asked to articulate, in non-monetary terms: What is this piece worth? What might someone do or give to access it? And what would they, the artist, like to receive in return? Might a transaction be as much about generosity, reciprocity or wit, about sharing a moment, an idea or a joke, as it is about fair payment? Does it matter if the price is somehow equal to the labour of producing the artwork? In this way, each piece becomes a small gift to be “repaid” in reciprocal acts, initiating a reflection on what we each value in art, culture and relationships.

This type of discussion is certainly not new to artists and cultural thinkers. From Warhol to Duchamp to Edward Kienholz’s trade watercolors, the canon is filled with artists prodding at the absurdity of art sales, destabilising the tenuous edifice on which their livelihood depends. More recent interventions include Kenya Robinson’s 2013 Remitting Default: a Psycho-Economic Performance of Getting Skoooooled, which records and publishes “the artist’s two-year experience as a Black MFA student at Yale University while struggling to maintain her personal finances and secure fiscal support.” Valentina Karga and Pieterjan Grandry’s 2016 Market for Immaterial Value is a small coin-like sculpture in which people can buy equity, thereby making “the sum of all individual investments determine the total value of the artwork.” Collectively owned, a community determines together whether to keep it or sell it. Perhaps most effectively, many current artists with social/relational practices work to circumvent the hierarchy and exclusivity of the art world altogether, diverting funds to invest directlyin their communities instead.

SUMMAEVERYTHANG is a community-based project started by artist Lauren Halsey in 2020 to invest in the place she grew up, delivering organic produce from Southern California farms to South Central L.A. (Image copyright: summaeverythang.org)

The practical ambivalences of art and commerce are well articulated in a 2016 interview with Martine Syms, in which she responds to a question about her use of the term “conceptual entrepreneur.”

“When I came up with that term...I was running Golden Age, a project space in Chicago, and people were always asking me. ‘Is this part of your practice?’ And I was like, no. I was cleaning cigarettes off the sidewalk; it was hard for me to glamourise it. I felt like a small business owner… I think my main interests and ideas have always come from independent music, black-owned businesses, and the idea of self-determination through having a sustainable institution, through institutionalizing yourself. Now I’m more aware of the problems and theoretical issues with that. And obviously, with the tech industry, where entrepreneur has kind of a horrible air surrounding it, I’m definitely more conflicted. But I’m still very interested in self-determination and being able to actually survive doing the work I want to do. So it’s important to talk about some of the things I’m doing as labor, as work, but I also understand the limitations of that and of using that language. I’m not resolved on it now.”

Fumbling to pin down the ever-slippery contradictions of art and capitalism, I take a detour to revisit Andrea Fraser’s 2005 essay From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique. In this text, Fraser discusses contradictions within a specific art-historical movement (“institutional critique”) that precedes and informs her own practice, but her analysis contains useful implications for The Whole Sell. Perhaps most relevant is Fraser’s reflection on the attempt to escape a system in which one is clearly embedded, in order to criticise it: the question of critique from within. This struggle to reconcile the deep entanglements of art and commerce, to make objects and meaning outside—or ‘alongside,’ or ‘in opposition to’—capitalism, finds The Whole Sell, like Fraser, “enmeshed in... contradictions and complicities, ambitions and ambivalence.” Furthermore, in a manner that might help account for artists’ persistent attraction to the WEC, Fraser reports “a certain nostalgia for institutional critique as… an artifact of an era before the corporate megamuseum and the 24/7 global art market, a time when artists could still conceivably take up a critical position against or outside the institution. Today, the argument goes, there no longer is an outside.” Ah, the good old days of simple sixties counterculture, back when there was an “outside.” Or, at least, when some of us still believed there was an outside.

Confronting entrenched alliances between art and capital, the impulse to abandon ship is powerful. And for Fred Turner, the transformation from “counterculture to cyberculture” as narrated through the trajectory of Whole Earth-affiliated projects, was also shaped by this inside/outside dilemma. In the late-sixties, New Communalists had attempted to abandon ship: to exit society and politics and go live in the woods by their own rules. In the 70s, as the economy crashed, youthful energy and trust-funds dried up and communes ran into crises of personality and management, the vanguard of the counterculture came crawling back to the boat. Is there another way? In the emerging ideology of “second wave cybernetics,” minicomputers, and eventually networked computing (the Internet), were embraced for their potential to decentralise power, share knowledge and build community. Evangelists like Stewart Brand believe that these technologies, originally developed by the military-industrial-academic complex, could be used in alternative, emancipatory ways. As Turner describes, radicals of the 70s and 80s “could accept their own increasing need to collaborate with mainstream society as a variation on the truth that no one could live outside “the system.” (Turner)

For Andrea Fraser, as well, the inside/outside paradox is not a reason to stop trying. “Now, when we need it most, institutional critique is dead, a victim of its success or failure, swallowed up by the institution it stood against,” she laments. In this spirit, The Whole Sell makes a modest appeal to not get swallowed up. Rather than indefinitely sulking around in a murky event horizon, The Whole Sell proposes a few (tentative, ephemeral) alternatives.

As an artist with a significant stake in ideas, critique and resistance, I’ve long felt averse to selling work as either luxury commodity or populist amusement, but this does not mean that I have no ambition to share my work. The Whole Sell provides a platform for distributing art outside of commerce and asks participants to define value in concrete, non-monetary terms. What other kinds of exchanges between artist and audience could constitute a transaction? How else might we understand consumption in relation to the intellectual, aesthetic, even subversive “products” of our labour? And how useful is the metaphor of online shopping—with it’s familiar lexicon of carts, customer service and captchas? Perhaps most interesting are the moments in which these conventions cease to function, unfit to contain the mush of subjectivity that must be crammed into boxes meant for pricing and order history.

Art is not peculiar for its function as commodity production, but only in its denial of that function. I relish the blow that Fraser deals to the guarded integrity and exceptionalism of art. “Every time we speak of the ‘institution’ as other than ‘us,’" she writes, “we disavow our role in the creation and perpetuation of its conditions… It's not a question of being against the institution: We are the institution.” But if we are the institution, how then should we go about critiquing ourselves? Can this reflexivity constitute meaningful action, can it move towards change? Or is it simply a way of making us feel better about our work?

As an artist, I often find myself longing for a kind of ideological purity, a desire shared by activists, intellectuals, and idealists of all stripes. As Audre Lorde argued in her 1982 speech Learning from the Sixties, “We were poised for attack, not always in the most effective places. When we disagreed with one another about the solution to a particular problem, we were often far more vicious to each other than to the originators of our common problem.” Listening to progressives today bemoan the fractured, self-destructive in-fighting of their peers, we might understand the artist’s ideological scramble for an uncompromised position as, at times, similarly counterproductive. I certainly understand the desire to cleanly escape a system that you’re trying to destabilise; it’s pragmatic, like exiting the building that you just set on fire. But in her analysis of institutional critique, Andrea Fraser seems to argue that getting “outside” the institution might not even be the goal. In her words, “what we do outside the field, to the extent that it remains outside, can have no effect within it.”

“Representations of the "art world" as wholly distinct from the "real world"...maintain an imaginary distance between the social and economic interests we invest in through our activities and the euphemized artistic, intellectual, and even political "interests" (or disinterests) that provide those activities with content and justify their existence. And with these representations, we also reproduce the mythologies of volunteerist freedom and creative omnipotence that have made art and artists such attractive emblems for neoliberalism's entrepreneurial, "ownership-society" optimism.” (Fraser)

Fraser’s “volunteerist freedom” and “entrepreneurial optimism” thrives within the weird and brainy pages of the Whole Earth Catalog. In typically down-to-earth terms, Kevin Kelly, one of the Catalog’s editors and the founder of Wired Magazine, described the project’s early days when Stewart Brand was selling products out of the back of his truck:

““Here’s a tool that will make drilling a well, or grinding flour, easier,” Brand would tell [the hippies,] pointing it out in his catalog of recommended tools. But his best selling tool was the catalog itself, annotated by him, featuring tools that didn’t fit into his truck.”

It’s interesting to note the interchangeability of “tool” and “catalog” here: the former, a thing that makes, the latter, a thing that sells. By studying this subtle conflation, we can gain a lot of insight into the evolution of consumer technologies post-WEC. From the advent of personal computers to the Internet to YouTube, each new technological breakthrough arrives with the promise of revolutionising one’s access to tools, and ends up providing, more often than not, access to sales. Far from the self-empowering “tool” promised by the cybernetic revolution, an iPhone today is no more effective as a means of creation or communication than it is a tool for consumption. Following the business model of giants like Google and Facebook, every “free” service or network we’ve come to rely upon operates as a front for massive global industries in advertising and data collection. There’s no such thing as a free social network, a free search engine, or a free lunch. This is what we call the whole sell.

Access to Tools_

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

A closer look at one of Audre Lorde's most famous texts provides a useful rethinking of building and demolishing, inside and outside. While Lorde was writing about interlocking architectures of white supremacy, patriarchy and homophobia, it is not hard to imagine her metaphor extending to the inescapable conditioning of life under global capitalism. I'd like to be careful here appropriating her use of "master" which invokes the particular brutality of chattel slavery in the Americas. At the same time, Audre Lorde’s intellectual contributions are critical to the development of what we now call ‘intersectional’ analysis. She draws an alliance between “those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference... who are poor, who are lesbians, who are Black, who are older,” stretching the term "master" to encompass many forms of oppression. Furthermore, there are many ways in which our present techno-capitalist class can be understood as descendants and perpetrators of white supremacy, settler colonialism and grotesque wealth accumulation. This lineage has granted a tiny minority of individuals inordinate power to develop the technologies that structure all of our lives, with minimal democratic regulation or community oversight. Time and time again, their tools have proved supremacist, authoritarian or exploitative (see: search engine bias, surveillance architectures, misinformation). These realities build a strong case for thinking about social networks, smart devices, e-commerce, and other recent innovations as a set of "master's tools."

Lorde's speech was written to call out white feminists who, in ignoring or silencing challenges posed by Black & queer feminism, ended up aligning themselves with white-hetero power structures. This accusation, she argues, would only be “threatening to those women who still define the master's house as their only source of support.” Here we can understand a clear distinction between inside and outside. In critiquing the injustice of patriarchy, homophobia, racism and ableism, the boundaries of the “master’s house” are somewhat defined. While the psycho-social effects of oppression shape all of us, and it can be argued that no one is immune or unaffected by them, in these instances, the notion of a space/perspective/community “outside” is also tangible and real. For instance, Black people exist, in some ways, outside the racist master’s house; queer people exist outside the hetero master’s house. Walls erected by the master himself to keep certain groups out, help to clarify when we are standing on the lawn. And the complex perspectives of such “outsider” subjects have been well-articulated by great thinkers like Lorde herself. In contrast, I find it more challenging in my current time and location to locate tangible space “outside” of global capitalism and technological hegemony; no one I know inhabits this space except in their imagination.

In her scathing critique of the NYU conference to which this speech was first given, Lorde called into question the way the conference was organised, who was invited to speak, and how her own inclusion had been orchestrated (last minute, tokenised—it's a prescient story for many QTBIPOC today). To Lorde, it is not simply the talks and papers that should be scrutinised, but also the process and the framework—the means as well as the ends. "What does it mean when the tools of a racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy?" Lorde asks. To extend this question to The Whole Sell: what does it mean to repurpose conventions of online mega-retailers and platform capitalism in order to examine the dynamics of art production and labor? As Fraser might suggest, is “within” the best position (and/or the only effective position) from which to critique?

For me, Audre Lorde’s statements also seem to haunt the practices of artistic appropriation, satirical readymade and institutional critique that are central to contemporary art as we know it, and to The Whole Sell as well. When artists misuse or subvert “master’s tools,” does this begin to constitute a demolition, or just a superficial renovation? Obliqueness, ambiguity and ambivalence are attributes cherished by many people who make and look at art. It could even be argued that “art” is one of the few disciplines that protects and makes space for such complexity and tension. In the face of urgent injustice (for instance, starvation wages, tech monopolies, surveillance technology) might this appetite for contradiction leave behind an aftertaste of complacency or even betrayal?

Applying Audre Lorde’s words in such a broad manner can begin to feel like a trap. Frameworks inherited, designed and funded by those in power will never be repurposed to burn that structure down—nor even, to take it apart brick by brick. And it would be foolish to insist that we live anywhere but here, squarely inside (à la Fraser) the master’s house: we use smartphones, we drive cars, some of us even periodically resort to buying something on Amazon. However, Lorde’s language offers agency in the creation of new tools, designed by new people, with new objectives in mind. Tool design and tool use are processes that must be held under perpetual scrutiny, in a turbulent state of becoming and unraveling. In her essay Seeing, Naming, Knowing, Nora Khan corrects James Bridle’s claim that “we need to re-enchant our tools.”

“It would seem “re-enchanting” is the wrong word, unless it means not further mystifying our tools. Instead we need to make them very sensible to us, and make critical thinking essential to “activating” them.” (Khan, emphasis mine)

Inspired by the critical words of Lorde, Fraser, and Khan above, The Whole Sell has been engineered as a kind of tool, providing an alternative framework for art distribution, valuation, exchange and interaction. The project borrows aesthetics and language from the Whole Earth Catalog, from art sales, and from any ordinary Shopify web-store, but reconfigures them to function neither in the service of selling, nor in upholding models of “success” based on competition and scarcity. In The Whole Sell, “buyers” can find tools suited not just for construction, but perhaps more importantly, for deconstruction.

This essay also recognizes the limitations of projects like The Whole Sell, and, more generally, the impulse of artists to confront real world problems by “making art about them.” To push beyond such limitations would likely require dissolving the hazy exceptionalism that sets artists apart from other workers. In doing so, “professional” artists would be unable to sustain their current privatization of talent; it would be necessary to abolish, for instance, the aura of competitive MFA degrees that benefit a handful of artists by fetishising everything they touch. What kind of societal restructuring would be necessary to support all those who work and think as artists, rather than just a selected few? Surely the rewards of redistributing wealth and attention, of increasing access and survival, would outweigh the loss of our current art world hierarchy. What might be gained if artists were to see themselves not as uniquely talented individuals, but as caretakers, collaborators and organisers of a common future?

As workers in nearly every other industry can attest, the direct action needed to win rights and build power may not be achievable on the job (i.e., within the artwork itself). Rather, these achievements require the kind of committed, straightforward organising that has developed over hundreds of years through labour struggles around the world. Kerry Guinan, an artist quoted in Sarah Jaffe’s book, provides a passionate appeal for artists to engage in “after-hours” organising:

“The majority of people who work in the arts will identify themselves as liberal to left-wing, often radically left-wing. This is going from the poorest artists to the highest paid curators in institutions… But, if this is the case that we are a field in which everyone is all left-wing values, then why are we all agreed that the art world is a piece of capitalist shit that is relying on private capital that exploits its workers, that exploits artists, relies on unpaid labor? This, to me, is living proof that art cannot change the world and that is why we need to organize. Artists need to realize how little power we all really have and how power needs to be built. It doesn’t come naturally and it is not a divine gift you get by being an artist.”

The world around the Whole Earth Catalog has shifted dramatically since the time of its publication. This fact is as apparent to Stewart Brand as to anyone reading this essay. As a 19-year-old undergraduate, Brand was ready to defend “individualism” with his life; in 1968 the first Whole Earth Catalog was published, promising to outfit and inform the self-made man; but only seven years later, shortly after the collapse of the New Communalist movement, he adopted a very different tone:

““Self-sufficiency” is an idea which has done more harm than good. On close conceptual examination it is flawed at the root… It is a charming woodsy extension of the fatal American mania for privacy… It is a damned lie. There is no dissectable self. Ever since there were two organisms life has been a matter of co-evolution, life growing ever more richly on life... We can ask what kinds of dependency we prefer, but that’s our only choice.”

What might prompt such a dramatic reversal? In opposition to Cold War state power and the cultural conservatism of the 1950s, the counterculture Stewart Brand helped to nurture took on conformity as its principal enemy. But is all conformity bad? Might a system of agreements and commonly-held beliefs, if freely coordinated, also be called consensus? Even today’s most sophisticated theoretical writing around interdependency and entanglement (ex. Donna Haraway, Anna Tsing, Karen Barad) seems to rest on some terrain of shared experience. Without sacrificing individual agency or obliterating diversity, it might be time to ask ourselves as artists: what kinds of dependency do we prefer?

In recent years, a wave of critical technology theorists have upended what Nora Khan calls the “feel-good, individualist techno-libertarian sentiments” dreamt up by Silicon Valley and it’s ‘countercultural’ forebears. In the tradition of abolitionist movements, these writers’ goals are not simply to destroy, but to create something better: to “craft the worlds [we] cannot live without, just as [we] dismantle the ones we cannot live within.” (Ruha Benjamin) Rather than bow down to the deterministic “gospel of the tool,” they advocate for alternative processes that are participatory, transparent and shapeable, restoring the “dignity and complexity of the imaged and imagined, with encoded sensitivity to context and historical bias.” (Khan) Alongside Nora Khan, Safiya Noble and many others interrogating the white supremacist/colonial/ableist underpinnings of our current technocracy, Ruha Benjamin thoroughly takes up this scholarship in her 2019 book Race After Technology. In it, Benjamin helps to articulate ways that new tools and processes can be activated by collective imagining:

Abolitionist tools are predicated on solidarity, as distinct from access and charity. The point is not simply to help others who have been less fortunate but to question the very idea of “fortune”: Who defines it, distributes it, hoards it, and how was it obtained?... Solidarity takes interdependence seriously. By deliberately cultivating a solidaristic approach to design, we need to consider that the technology that might be working just fine for some of us (now) could harm or exclude others and that, even when the stakes seem trivial, a visionary ethos requires looking down the road to where things might be headed. We’re next.

Here Benjamin evokes a very different “we” than the WEC’s “we” that was discussed earlier, but it’s important to notice how her conception of solidarity still pushes outside of her own experience in an expression of radical inclusion. Regardless of who you are, and the particular vectors of privilege and oppression that affect your life, there’s always “others” who may be “harmed” by exclusion from your vision of an abolitionist future. In a 1998 interview, Toni Morrison approaches collective imagination using terms that recall our earlier discussion of inside/outside dynamics: “All paradises, all utopias are designed by who is not there, by the people who are not allowed in.” It seems that exclusion, if it doesn’t entirely crush the body or spirit, can become a motivator for visionary imagining. But what if one’s own exclusion or harm isn’t readily discernible? What if it is hidden behind a veneer of technocratic objectivity, behind the impenetrable mask of ‘neutral’ tools? In her statement above, Ruha Benjamin is pressing Stewart Brand’s assessment of “co-evolution” one step further. To her, interdependence means that our attention to, inclusion in, and comprehension of digital tools are not lofty ideals, but a matter of common survival. If we ignore the injustice inflicted on “others” by new tech design and implementation, we will all be next.

Whole Earth Catalog

The Whole Sell - Click here to visit